Why the study of the arts and culture should never be underestimated

In recent years, I've witnessed a decline in the public conviction that the arts and culture - and, to extent, the humanities - are important. Even in such a free-speaking, educated, progressive country such as mine, there has - seemingly - been 'doubts' and discussions about how much value we should place on the arts and cultural studies in times of economic crisis. Almost as if the government and general public have...forgotten why culture is important, especially in times of crisis, and despite being avid consumers of it themselves.

Several politicians in government in my country have long been patronizing towards the subject and the study of it, which has left half of academia - aka the humanities - at a loss for decades now. We've experienced cutback after cutback from the government, with vital studies being carelessly shut down for longer periods or even permanently. We've been told again and again that the humanities are all just 'chatty studies'; apparently too broad and abstract to generate concrete jobs or any concrete results in real-life. So much and for so long, it has sown doubt in the very hearts of their students and let the studies become something to be ashamed, apologetic or defensive of and not something worth aspiring towards since 'you'll get no concrete job title or skills afterwards'.

Several scholars have actually been compelled to go out and defend the study of the arts through articles, interviews, talks and even entire books entitled 'Why the arts/humanities are important' etc.. Apparently the government has been so keen on all their 'concrete results'-talk that only 'documented' and consistent expert proof would be enough to convince them. And not even then..!

Shocking, I know. Almost offensive that we should even have to prove and defend the humanities - the very idea of culture!

At least to me - as an art history major.

It feels personal because I regard the arts - the production as well as the scholarly part of it - to be just as important as any other field of science. After all, the term 'science' is used rather liberally on a daily basis ('culture' as well, but that's a whole other talk for another time). In academia, for example, science doesn't just apply to STEM, the study of math, nature and physics. Humanities are a scientific field, too. Actually, humanities cover all of the above; human life, history, understanding and self-expression; the very workings of our consciousness that lead to the discoveries within physics, engineering, etc.. And vice versa, of course.

Because life is not as conveniently divided and studied separately as in academia. The latter is only structured so for pure pragmatism and bureaucracy, in order for people to specialize in the specific subject(s) they are interested in. That doesn't mean life can only be valued from separated categories and thus separate sets of values, especially not in a hierarchical order. Sure, medicin and law are undoubtedly pivotal for a society to survive without turning into death and anarchy. But life isn't just about surviving, it's about living. And here all the rest of academia matters just as much. Without culture, anarchy would ensue just as well. Through humanities we learn to understand ourselves, not just nature, the laws of gravity or how machines operate. It is all connected after all; how we adapt, create, interact and evolve as humans and how we make use of the earth we live on and our changing surroundings. How what we create affects and influences us and our surroundings and vice versa, through time, space and a collective mentality.

I am, frankly, in disbelief that people even have doubts about the value of the humanities, since the very word suggests an inescapable part of life itself: human-ity, ourselves. If there were no humanities there'd hardly be any humanity in humans left. Maybe that's subjectively speaking. But culture also reflects our self-understanding and self-expression; what we want to be as human beings and what world we want to live in. It suggests freedom of speech and expression and without censure. Of democracy. However disappointing it may be at times, true democracy is still the only form of government that allows for change, freedom, opportunity and choice. Dictatorships and totalitarian states and fascistic ideologies do not and whatever culture or even 'art' these produce, it will always be restricted, censured, controlled and oppressed. A world lived in fear. Culture itself has paved the way to show us just so; books like '1984', 'Fahrenheit 451', 'The Handmaid's Tale' etc. show us what would happen if we condemn or restrict culture in its most democratic sense.

And, too often, reality surpasses fantasy. Today, our historically systemic flaws have come back to bite us in the ass, to speak plainly. Decades of racism, sexism, the oppression and criminalization of LGBTQIA+ community etc. have been taken up to revision with good reasoning, yet also used for all manners of crusading with the help of the digital age, for better or for worse. And where democracy can offer diplomatic change to these mistakes, it is often prolonged and unnoticed, bogged down by bureaucracy and lobbyism. At its core, democracy is, after all, about freedom of speech, giving room to all kinds of contrasting opinions, and with solutions often based on communication and compromises. I believe this is one of the reasons why - much to the surprise of the majority and the experts - identity politics and populism have become increasingly popular, especially in recent years. They offer a more immediate, non-negotiable 'fix' to the need for radical change and threaten to assume democracy (there are some very fine lines in-between that easily evade one's eyes, I've come to realize). That, combined with long-reaching consequences of the global financial crisis, continued war and terror setting off an influx of immigration, socio-political unrest and divide, increased nationalism and fascistic movements. Already, our day and age has been compared to that of the early 20th century and there's a jarring truth to the parallels.

I think it's safe to presume that those of us who who have lived in what we've defined as democracy for some time now (remember, historically, democracy is still quite young) have become perhaps too accustomed to it. We've rested on our laurels. Because the only way to keep up the essence of democracy is never to rest on one's laurels. It demands constant work and revision; something I believe escapes the majority in a democratic society which is content (such as Denmark, my own country). The idea of something relatively extreme becoming the fine-tuned ideology of an entire government in a presumably democratic country is, frankly, ludicrous to most generations. If you know your history, you'll know how people reacted to the first whispers of Hitler's rise and a Second World War, only about two decades after the first one - with an contradictory mix of denial, disbelief and fearful resignation. While history may not repeat itself, it most certainly rhymes!

My parents and many of their generation and the following loudly scoffed and laughed at the fact of Trump running as a presidential candidate in the US back in 2015. They were utterly convinced it would never happen. Understandably so. And perhaps also very telling since previous generations are known to have greater faith in the system and the government than Millennials and Generation Z. And though I, too, instinctively reacted with laughing disbelief to Trump, I was vary to dismiss or scoff as easily at the idea actually coming to fruition. Well, it is easy to be wise after the events, but even back then, it felt like we were entering an era where anything could happen. Something simmering in the air. A national unrest; a frustration that wasn't easily pronounced or grasped or understood. But it felt like something was about to culminate that hadn't already culminated. Already then, right-wing extremist parties were forming and marching throughout many European countries; the frustration spurred from the economic crisis (among other things, as mentioned above), leading to even greater social inequality and political disruption. Highly educated people openly rationalized and fine-tuned extremist ideologies on television and ran as politicians. This urgent need for extreme change could no longer be dismissed as an unintelligent mob reacting. It was sickening to watch.

Even such liberal and culturally pioneering countries as France had figures like Marine Le Pen running for president; a wolf in sheep's clothes, backed by nearly half of the population at their latest election - and by Mussolini's frigging granddaughter, 'no less'! Though, luckily, Le Pen didn't win (this time), it was a close call. Too close.

Britain - one of the founders of the European Union - too seemed at a loss about the growing and alienating wishes of its people and its relationship to the rest of the world. It eventually led to the disastrous and grossly misguided Brexit. An exit with far-reaching consequences they had no concept of and are likely regretting now, many already protesting in the streets.

Even my country was shocked by its own and unforeseen divide in its last election when almost half the country voted for our most far-right, xenophobic political party. And just like some Americans did later on, many of my peers threatened to move to another country; half in jest, half in frustration, disgust and disbelief.

And then it was the Americans' turn. Just look how that went.

And through all of this, I couldn't help noticing the same patterns of reactions among people, journalists, politicians and socio-political experts in each country: Denial, disbelief, indignation and resignation. Some people, journalists, historians and experts had however predicted such outcomes; had actually warned us about it, and the fact that no matter how absurd and unlikely it all sounded, it had all happened before in some manner or another and with the same pattern of reaction. Still, though people read and regarded these point of views, many staunchly held the understandable but naïve hope that these theorists were wrong. That the people and the system couldn't possible allow it to happen! And in the end, it proved they couldn't have been more wrong! That, indeed, was a shock! And it sent everyone into a frenzy, asking and trying to understand how and why - WHY all of this could happen?!

And here - right here - those who have studied the humanities and even the arts come in! We may not sit with an answer to the definite solution of such societal unrest, but at least we have studied the human history; the human understanding and behavior in all categories of society that may have led to and influenced this very change!

To put into context, I had a professor at university who was invited to a summit in the European Parliament to speak about how the arts could influence society positively in regards of perhaps preventing right-wing extremist movements to rise, having my country as an example. It may sound idealistic and naive, but, as my teacher said, the European Union politicians seemed almost desperate, having tried every other measure and looked towards countries who didn't seem to be fighting the same kind of problems. (Ironic, since no country is entirely without such problems, but, in Denmark's case, not in such extreme ways.)

True, experts in economics have something to say as well since capitalism is a global driving force that influence many governmental, societal and historical patterns, for better or for worse. Unfortunately, capitalism is the governing system around the world and, given its parasitical nature, is too often misplaced and misused, even in democracies. Marx predicted it already in the 19th century.

But such complacency, or even complicity; believing the system itself would work against such ideological movements, is dangerous. History should be hard teacher, but unfortunately human memory only carry you so far. Living in the present, feeling frustrated beyond comprehension and wanting change - even of any kind! - makes it hard to rationalize your situation to that of the past. After all, you can only feel what you feel now, and that's also why identity politics and populism are so, well, popular.

What has and is happening now should teach you to never trust the system to be infallible nor the people to remain at ease and unchanged, no matter the context. Do not just assume, simply because you are relatively content. I say that to myself often - or as often as I can - because the human being is habitual and prone to follow the crowd that reflects its own lifestyle and values, sometimes forgetting the unrest that may dwell among all the rest.

As I said, I won't profess I have the solution for the world situation as it is, nor is it my intention to come across as a goody-goody who's sitting with all the knowledge to the arts and humanities, simply because I have majored in the field. The arts are not this holy, pure thing that will give all the answers. That would be counteractive to the very idea of arts and culture. The importance of it, and to come full circle, is: To produce it. To study it. Never seize. Never undermine the power of arts and culture and our continued interest in them.

I'll finish off with an excellent quote from the always excellent musician Philip Glass:

Several politicians in government in my country have long been patronizing towards the subject and the study of it, which has left half of academia - aka the humanities - at a loss for decades now. We've experienced cutback after cutback from the government, with vital studies being carelessly shut down for longer periods or even permanently. We've been told again and again that the humanities are all just 'chatty studies'; apparently too broad and abstract to generate concrete jobs or any concrete results in real-life. So much and for so long, it has sown doubt in the very hearts of their students and let the studies become something to be ashamed, apologetic or defensive of and not something worth aspiring towards since 'you'll get no concrete job title or skills afterwards'.

Several scholars have actually been compelled to go out and defend the study of the arts through articles, interviews, talks and even entire books entitled 'Why the arts/humanities are important' etc.. Apparently the government has been so keen on all their 'concrete results'-talk that only 'documented' and consistent expert proof would be enough to convince them. And not even then..!

Shocking, I know. Almost offensive that we should even have to prove and defend the humanities - the very idea of culture!

|

| Guernica - Picasso - Milan - 1953 |

It feels personal because I regard the arts - the production as well as the scholarly part of it - to be just as important as any other field of science. After all, the term 'science' is used rather liberally on a daily basis ('culture' as well, but that's a whole other talk for another time). In academia, for example, science doesn't just apply to STEM, the study of math, nature and physics. Humanities are a scientific field, too. Actually, humanities cover all of the above; human life, history, understanding and self-expression; the very workings of our consciousness that lead to the discoveries within physics, engineering, etc.. And vice versa, of course.

Because life is not as conveniently divided and studied separately as in academia. The latter is only structured so for pure pragmatism and bureaucracy, in order for people to specialize in the specific subject(s) they are interested in. That doesn't mean life can only be valued from separated categories and thus separate sets of values, especially not in a hierarchical order. Sure, medicin and law are undoubtedly pivotal for a society to survive without turning into death and anarchy. But life isn't just about surviving, it's about living. And here all the rest of academia matters just as much. Without culture, anarchy would ensue just as well. Through humanities we learn to understand ourselves, not just nature, the laws of gravity or how machines operate. It is all connected after all; how we adapt, create, interact and evolve as humans and how we make use of the earth we live on and our changing surroundings. How what we create affects and influences us and our surroundings and vice versa, through time, space and a collective mentality.

I am, frankly, in disbelief that people even have doubts about the value of the humanities, since the very word suggests an inescapable part of life itself: human-ity, ourselves. If there were no humanities there'd hardly be any humanity in humans left. Maybe that's subjectively speaking. But culture also reflects our self-understanding and self-expression; what we want to be as human beings and what world we want to live in. It suggests freedom of speech and expression and without censure. Of democracy. However disappointing it may be at times, true democracy is still the only form of government that allows for change, freedom, opportunity and choice. Dictatorships and totalitarian states and fascistic ideologies do not and whatever culture or even 'art' these produce, it will always be restricted, censured, controlled and oppressed. A world lived in fear. Culture itself has paved the way to show us just so; books like '1984', 'Fahrenheit 451', 'The Handmaid's Tale' etc. show us what would happen if we condemn or restrict culture in its most democratic sense.

|

| Werner Bischof, Picasso exhibition, Tokyo, 1951 |

And, too often, reality surpasses fantasy. Today, our historically systemic flaws have come back to bite us in the ass, to speak plainly. Decades of racism, sexism, the oppression and criminalization of LGBTQIA+ community etc. have been taken up to revision with good reasoning, yet also used for all manners of crusading with the help of the digital age, for better or for worse. And where democracy can offer diplomatic change to these mistakes, it is often prolonged and unnoticed, bogged down by bureaucracy and lobbyism. At its core, democracy is, after all, about freedom of speech, giving room to all kinds of contrasting opinions, and with solutions often based on communication and compromises. I believe this is one of the reasons why - much to the surprise of the majority and the experts - identity politics and populism have become increasingly popular, especially in recent years. They offer a more immediate, non-negotiable 'fix' to the need for radical change and threaten to assume democracy (there are some very fine lines in-between that easily evade one's eyes, I've come to realize). That, combined with long-reaching consequences of the global financial crisis, continued war and terror setting off an influx of immigration, socio-political unrest and divide, increased nationalism and fascistic movements. Already, our day and age has been compared to that of the early 20th century and there's a jarring truth to the parallels.

I think it's safe to presume that those of us who who have lived in what we've defined as democracy for some time now (remember, historically, democracy is still quite young) have become perhaps too accustomed to it. We've rested on our laurels. Because the only way to keep up the essence of democracy is never to rest on one's laurels. It demands constant work and revision; something I believe escapes the majority in a democratic society which is content (such as Denmark, my own country). The idea of something relatively extreme becoming the fine-tuned ideology of an entire government in a presumably democratic country is, frankly, ludicrous to most generations. If you know your history, you'll know how people reacted to the first whispers of Hitler's rise and a Second World War, only about two decades after the first one - with an contradictory mix of denial, disbelief and fearful resignation. While history may not repeat itself, it most certainly rhymes!

My parents and many of their generation and the following loudly scoffed and laughed at the fact of Trump running as a presidential candidate in the US back in 2015. They were utterly convinced it would never happen. Understandably so. And perhaps also very telling since previous generations are known to have greater faith in the system and the government than Millennials and Generation Z. And though I, too, instinctively reacted with laughing disbelief to Trump, I was vary to dismiss or scoff as easily at the idea actually coming to fruition. Well, it is easy to be wise after the events, but even back then, it felt like we were entering an era where anything could happen. Something simmering in the air. A national unrest; a frustration that wasn't easily pronounced or grasped or understood. But it felt like something was about to culminate that hadn't already culminated. Already then, right-wing extremist parties were forming and marching throughout many European countries; the frustration spurred from the economic crisis (among other things, as mentioned above), leading to even greater social inequality and political disruption. Highly educated people openly rationalized and fine-tuned extremist ideologies on television and ran as politicians. This urgent need for extreme change could no longer be dismissed as an unintelligent mob reacting. It was sickening to watch.

Even such liberal and culturally pioneering countries as France had figures like Marine Le Pen running for president; a wolf in sheep's clothes, backed by nearly half of the population at their latest election - and by Mussolini's frigging granddaughter, 'no less'! Though, luckily, Le Pen didn't win (this time), it was a close call. Too close.

Britain - one of the founders of the European Union - too seemed at a loss about the growing and alienating wishes of its people and its relationship to the rest of the world. It eventually led to the disastrous and grossly misguided Brexit. An exit with far-reaching consequences they had no concept of and are likely regretting now, many already protesting in the streets.

Even my country was shocked by its own and unforeseen divide in its last election when almost half the country voted for our most far-right, xenophobic political party. And just like some Americans did later on, many of my peers threatened to move to another country; half in jest, half in frustration, disgust and disbelief.

And then it was the Americans' turn. Just look how that went.

|

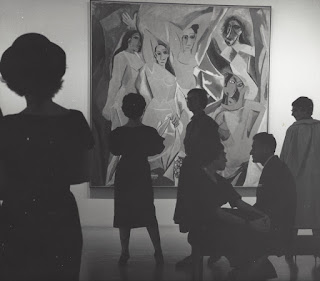

| Kees Scherer - Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso. MOMA New York City 1959 |

And here - right here - those who have studied the humanities and even the arts come in! We may not sit with an answer to the definite solution of such societal unrest, but at least we have studied the human history; the human understanding and behavior in all categories of society that may have led to and influenced this very change!

True, experts in economics have something to say as well since capitalism is a global driving force that influence many governmental, societal and historical patterns, for better or for worse. Unfortunately, capitalism is the governing system around the world and, given its parasitical nature, is too often misplaced and misused, even in democracies. Marx predicted it already in the 19th century.

But such complacency, or even complicity; believing the system itself would work against such ideological movements, is dangerous. History should be hard teacher, but unfortunately human memory only carry you so far. Living in the present, feeling frustrated beyond comprehension and wanting change - even of any kind! - makes it hard to rationalize your situation to that of the past. After all, you can only feel what you feel now, and that's also why identity politics and populism are so, well, popular.

What has and is happening now should teach you to never trust the system to be infallible nor the people to remain at ease and unchanged, no matter the context. Do not just assume, simply because you are relatively content. I say that to myself often - or as often as I can - because the human being is habitual and prone to follow the crowd that reflects its own lifestyle and values, sometimes forgetting the unrest that may dwell among all the rest.

As I said, I won't profess I have the solution for the world situation as it is, nor is it my intention to come across as a goody-goody who's sitting with all the knowledge to the arts and humanities, simply because I have majored in the field. The arts are not this holy, pure thing that will give all the answers. That would be counteractive to the very idea of arts and culture. The importance of it, and to come full circle, is: To produce it. To study it. Never seize. Never undermine the power of arts and culture and our continued interest in them.

I'll finish off with an excellent quote from the always excellent musician Philip Glass:

"When things get out of balance, the arts come in and bring the human side back. Without that, our societies would be prisons. They wouldn't be able to renew themselves."*

Comments

Post a Comment